What Were the Creeds Really For?

The Creed That Unites: Remembering Our Shared Story

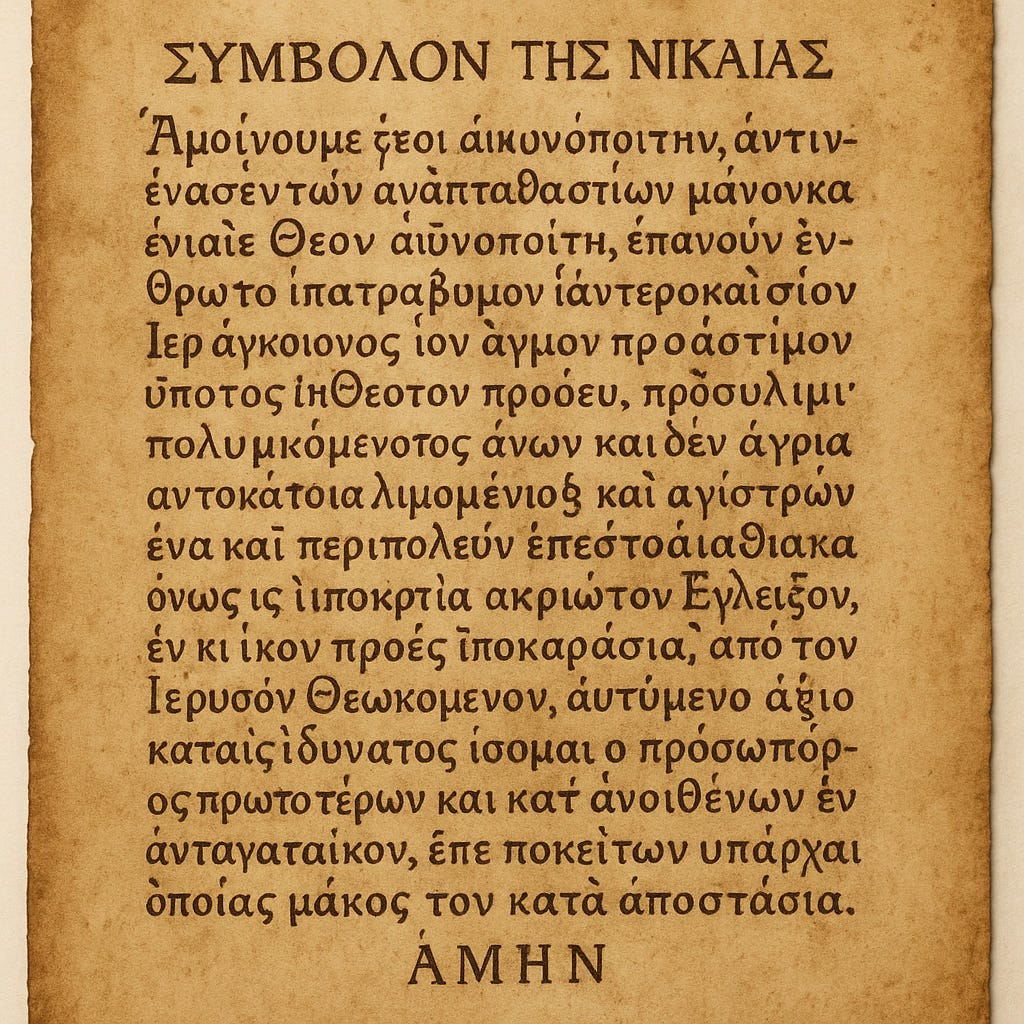

Back in seminary, while studying church history, I remember beginning to grasp why the early church felt compelled to write down creeds. They weren’t simply flexing theological muscle or laying down rigid rules. They were trying to respond thoughtfully and pastorally to what they saw as real challenges to the faith. The creeds emerged not just as rebuttals to heresy, but also as tools of discipleship, anchoring new believers in a shared understanding of who Jesus is and what it means to follow Him in a world full of competing claims.

That still makes sense to me. But as I revisit those early formulations now, I find myself sitting with the question: How should we approach the creeds today, knowing both their historical role and the ways they’ve been used since?

The Creeds Were Pastoral, Not Just Doctrinal

It’s easy to forget that the early church didn’t yet have a neatly packaged New Testament or a universal way of explaining the Trinity. What they did have were stories about Jesus, the experience of the Spirit, and the need to stay rooted in what had been handed down.

The creeds arose from this crucible of necessity. The church was clarifying what it meant to follow the crucified and risen Christ, distinguishing the Christian story from Gnostic speculations, imperial ideologies, and theological shortcuts that undermined either Jesus’ divinity or His humanity.

They weren’t written in ivory towers. They were forged in the life of the church through prayer, conflict, Scripture, and community. At their heart, the creeds were declarations of worship before they became instruments of policing.

What If the Other Views Had Won?

This is something I used to wonder about. What direction might the church have taken if the more “alternative” views of Jesus, the Trinity, or salvation had shaped the core tradition instead?

It’s a valid question, especially when those early debates were not only theological but also political and cultural. Still, most of the early church wasn’t trying to suppress honest disagreement for the sake of control. They were convinced that certain views, however sincere, couldn’t sustain the good news of the gospel.

Even so, we would do well to remember that many of the “losing sides” were not malicious but thoughtful, sincere, and searching. This should give us a posture of humility, not superiority. Because the truth is, the church has always been more diverse, more complicated, and more contested than we tend to admit.

Were the Creeds Ever Meant to Exclude?

Over time, the purpose of the creeds shifted. What began as statements of unity and worship became, in some places, boundary markers used to determine who was in and who was out.

I don’t think the early church fathers imagined that their creeds would one day be wielded to enforce rigid uniformity. I don’t think they intended to use them to silence nuance or shut down honest wrestling. At least, not in the way it often happens today.

They were trying to protect a fragile and growing faith community. Today, however, creeds can be weaponized and used not to shepherd but to sort, not to teach but to divide. And that’s not faithfulness to their original spirit. That’s fear masquerading as certainty.

One Body, Many Expressions

When we look at the history that followed from East and West, to Protestant and Catholic, to the hundreds of denominations we see now, it’s tempting to feel discouraged. How could one faith fragment so much?

But maybe we’re asking the wrong question.

Paul’s image in 1 Corinthians 12 speaks of one body, many parts. What if we saw denominational differences not only as divisions but also as different organs — each offering something vital, even if incomplete? Some traditions remind us of holiness. Others embody grace. Some hold to sacrament. Others to Scripture. Some treasure tradition. Others lean into renewal.

No one tradition holds everything. But together, they might point more fully to the mystery of Christ.

So, What Do We Do with the Creeds Now?

Maybe we return to them not as checkpoints, but as prayers. Not as test questions, but as shared declarations of trust. Not as the last word, but as part of the church’s ongoing conversation.

We can honor their purpose without idolizing their form. We can let them shape us without letting them limit us. We can receive them as wisdom from the past, not as tools to gatekeep the future.

Final Thought

The church has never had a neat story. But it has always been carried through tension, through disagreement, through grace.

Maybe the creeds still belong, not because they settle every question, but because they remind us of what has always been central:

A crucified and risen Christ.

A Spirit still speaking.

A faith handed down in hope.

A body, still learning how to live as one.

Reflection Question:

How have creeds shaped your view of faith, and how might they be reclaimed? Not to control belief, but to anchor it in a shared story?

This reflection was originally published on Medium under the “Even Here” publication.

Read it there → Even Here